Nearly ten years ago, the most ambitious climate agreement to date was signed at the COP21 in Paris to tackle climate change. It set a clear target (keeping global temperature rise well below 2°C, preferably to 1.5°C compared to pre-industrial levels), was legally binding (at least in theory), and has since been ratified by a large majority of nations (with the exception of Iran, Libya, Yemen and the USA twice under Trump I and II).

However, the world in 2025 is very different to what it was in 2015 and at first glance there won’t be much to celebrate at the COP30 this week. The objective of keeping temperature rise under 1.5°C will not be achieved and carbon emissions worldwide have continued to increase since 2015, broadly at the same rate.

Perhaps more worryingly, the world is more fragmented than it was ten years ago (making cooperation between nations more challenging), the focus of G20 countries has shifted to more immediate priorities (e.g. defence spending has soared in the last few years) and the political consensus around climate change has significantly weakened.

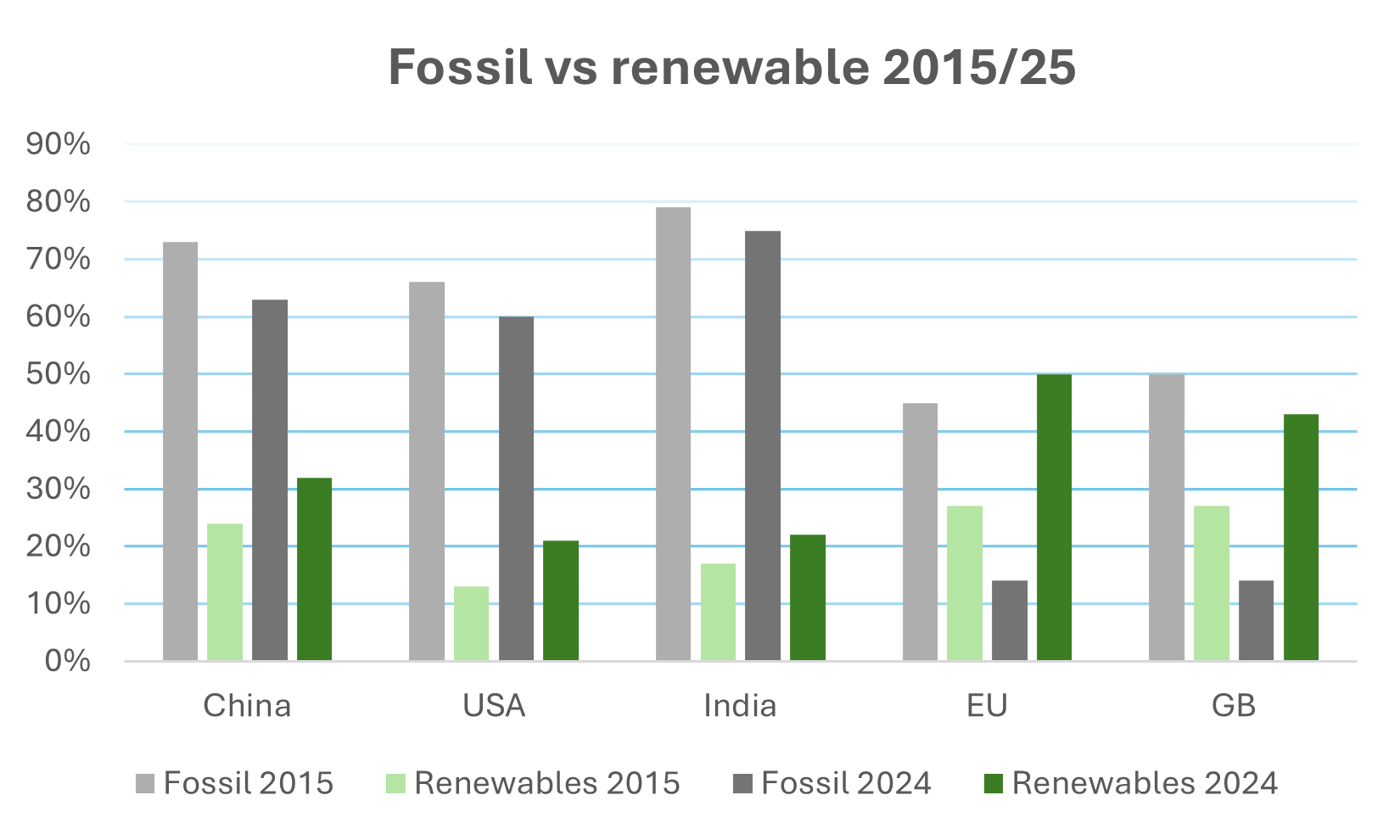

This is not what delegates of the Paris Agreement were hoping for ten years ago. And despite clear progress in most countries (with Europe and a few other countries leading the way), progress achieved by the largest CO2 emitters (China, USA, India) has been far too slow to reduce our dependence on fossil fuels in the short-term – see figure 1 below.

Reasons to be optimistic

There are however a few reasons to be optimistic. For a start, this will be the first COP held in Brazil since the original Rio Earth Summit in 1992, which marked the beginning of a (slow) awareness process around climate change.

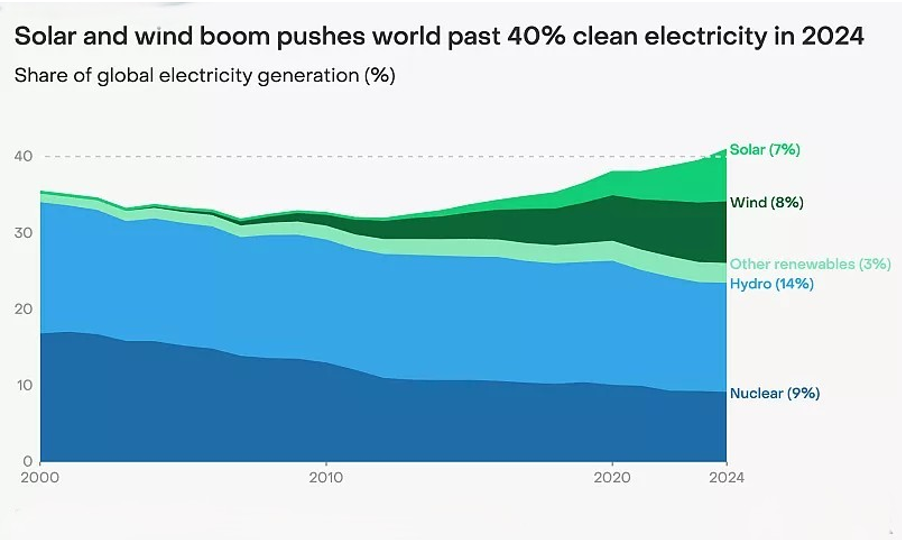

More importantly, solar and wind power have clearly surged worldwide since 2015 (as shown in the figure 2 below).

There are major differences between regions of course, but it is growing at an exponential rate almost everywhere.

Outside Europe and a few other mature markets, many countries in Africa and the Middle East are very rapidly developing solar power (Saudi Arabia for example has the objective of increasing production of solar power from 4 GW to 130 GW by 2030).

The key problem for now is that fossil fuels remain a well-known (and reasonably cheap) way of producing vast amounts of energy, and there are enough reserves of oil and gas for at least 50 years (and coal for perhaps 100 years). More fundamentally, our entire global economy over the last two centuries has been based on extracting fossil fuels and very successful in taking a vast number of the world population out of poverty.

And while we are de facto transitioning to a new energy system (less carbonised, more digitised and more flexible) it feels painful because (a) very few countries have prepared for it, (b) our energy system needs significant investment to adjust to a shift in supply (with more intermittent sources of electricity) and a surge in demand (driven by AI) and (c) the political stakes are very high (which makes long-term planning more difficult).

It is therefore essential to take all sections of society with us on the energy transition and make end bills affordable for consumers – an effective energy transition will not succeed without this.

Looking ahead

There is no magic solution but perhaps some key principles around which a form of consensus could be built during COP30 and thereafter:

- Setting a realistic objective: While ambitious climate goals (such as the one set out in the Paris Agreement) have undoubtedly increased awareness of climate risks, triggering climate policies and significant investment, it has also antagonised views, making change more difficult. Furthermore, failure to achieve what was always an impossible target (keeping global temperature rise below 1.5°C) has not helped to build a positive narrative around the energy transition.

- Planning ahead: The example of the Chinese five-year plans will be difficult to replicate in other places. However, the focus of the 15th Chinese five-year plan (covering 2026-2030) on better integrating wind and solar power and improving real time response to fluctuations in power demand, indicates that if we don’t plan for the long-term, others will do and will get ahead of us.

- Changing the narrative: The invasion of Ukraine in 2022 has confirmed that committing to reliable and affordable access to energy is essential. While there are many reasons to be worried about the rise in temperature, we should recognise that fear of climate change alone does not work. A narrative based on what most people really care about – i.e. energy security and economic growth – will be more likely to succeed.

Conclusion

While the energy transition has been too slow to achieve the objectives set out ten years ago in the Paris Agreement, and the geopolitical context is not exactly for resounding announcements to envisage the climate future optimistically, there are nonetheless objective reasons to be cheerful.

One way or another, most countries have started the transition, and our energy system will continue to become more flexible, less carbonised and more digitised - particularly given fossil fuels reserves are finite and will one day reach a level where it becomes cheaper to stop drilling.

Smart technology is playing an increasingly important role, giving more control to end-consumers over their consumption and allowing energy companies to better understand and manage the fluctuations in supply and demand on the energy grid.

Access to the increasing insight the digitisation of the energy system offers (for example via smart meters) is enabling more targeted investment and network optimisation. It will also continue to deliver greater value across the system in improving energy planning, addressing fuel poverty and enhancing network performance.

Perhaps the best reason to be optimistic is that recent studies have shown that, by a significant majority, people still support action to tackle climate change. Even in countries where there is a strong anti-climate change rhetoric at government level, things are usually moving in the right direction at local level.

The pace at which all of this happens remains uncertain (albeit it may happen faster than what we imagine today) but the key is how we choose to tell the story – a bit more on energy security and economic growth, and a bit less on the worst of climate change.

Stève Hervouet

Chief Strategy and Regulation Officer

You may also like